(Thinkstock)

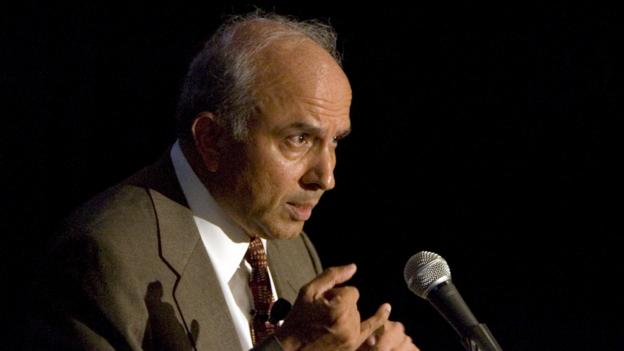

Is Prem Watsa nuts? That’s the question a lot of people are wondering these days after the Toronto-based billionaire made a $4.7 billion bid to take over BlackBerry.

Just three days before his September 23 proposal, the troubled smartphone maker said it was stuck with $1 billion worth of unsold phones and had to lay off 4,500 workers. Its share price has fallen 96% from its July 2007 high and the company is losing market share to competitors like Apple and Samsung every quarter.

There are doubts that Watsa’s bid will succeed, according to Reuters — and those doubts sent the stock down further to $8.10 on Wednesday, below the $9 per share offer Watsa’s Fairfax made. If the deal does happen, it may seem like a peculiar buy to many analysts and investors. But for Watsa, the fact that everyone thinks he’s lost it means he’s probably on the right track.

You have to be willing to sell if you’re wrong. — Dan Dupont

The Indian-born founder and chief executive officer of Fairfax Financial, a Berkshire Hathaway-like company that owns a number of insurance and investment businesses, is a value investor, much like Warren Buffett.

Value investors seek to make big bucks in large part by buying out-of-favour companies. It certainly has paid off for Watsa. He purchased part of the Bank of Ireland in 2011 when most people were staying far away from Europe, and he recently bought into a real estate company in Greece. Watsa has reportedly already made a 50% return on his Bank of Ireland investment.

While not all of his investments have worked out — he took losses on Montreal-based forestry company AbitibiBowater (now known as Resolute Forest Products), Winnipeg-based media company Canwest and he currently owns 10% of BlackBerry’s shares — he’s had far more hits than misses.

There’s a good reason why Watsa and Buffett take a value approach to investing and it’s the same reason why you should consider it, too: the approach has proven to be more lucrative than other strategies.

Eric Kirzner, the John H Watson Chair in Value Investing at Toronto’s Rotman School of Management, recently looked at how much better value investing has done versus growth investing—a strategy that usually involves buying high-growth companies with rapidly expanding earnings.

He compared returns on the Russell 1000 value index and the Russell 1000 growth index since 1979 and found that value beat growth by 1.6% per year on a compound annual growth basis. That translates into value stocks doing 71% than growth companies over the last 34 years “There’s clearly a premium on value investing over growth,” he said.

The concept of value investing is easy to understand, but hard to put into practice said Dan Dupont, a value-focused portfolio manager with Fidelity Investments.

At its most basic, it’s about buying when a stock is priced low and then selling when it is priced high. But most people have trouble making bets on companies that are down in the dumps.

“It entails investing in businesses that are not to be discussed at cocktail parties,” said Dupont.

Todd Johnson, a portfolio manager with Winnipeg-based BCV Asset Management, which owns Fairfax Financial debt, adds that value investors “have to ignore a lot of conventional wisdom and delve into unpopular investments.”

Here’s how value investing works: buy a company when it’s dirt cheap from a valuation perspective — compared to its peers and its historical performance —and then sell when the stock reaches what you think it’s really worth.

That means delving into ratios such as price-to-earnings, price-to-book and enterprise value-to-EBITDA and seeing if they have fallen below their historical norms, said Kirzner. EBITDA, an important indicator of a company’s financial performance, refers to earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortisation.

Typically, a company starts appealing to value investors when a particular sector is having trouble or a business has a few bad quarters and investors get spooked and sell.

Stick with quality

These operations, though, aren’t necessarily bad businesses. Dupont likes companies that can continue to grow their underlying value per share — that could be earnings or revenues or a number of other metrics. Warren Buffett likes to see “owner’s earnings” grow, which is basically the cash flow that’s available to shareholders.

As long as the company is still solid, the idea is that in time — and it could be a long time — some event, action or theme will bring investors back into the fold, said Kirzner.

“You have to believe that these companies can be rescued,” he explained.

The danger with value investing, however, is the “value trap.” That’s when valuations continue to fall and that catalyst for better performance never comes, said Dupont. Be wary of companies where values are shrinking rapidly, he said.

Another problem that value investors face is what Dupont calls “intellectual dishonesty.” Investors are often too optimistic about a stock’s chances and hold on to the idea that a company can be turned around when it’s clear it can’t recover.

“You can be infinitely patient, but don’t get disillusioned and think a business can be turned around when the facts tell you it can’t,” he says. “Admit when you’re wrong and turn your attention somewhere else.”

Margin of safety

Many people prefer the value approach because it can be a less risky way to play the market — and to curtail further losses. Since the company is already so cheap, you’re not losing much if it falls further.

There’s a “margin of safety,” said Dupont that allows investors to make mistakes. He describes this margin of safety as the price you pay versus what you think the company is worth. The bigger the gap between today’s price and the price it should be trading, the better, he said.

It’s not yet clear exactly what Watsa sees in BlackBerry, but with a cheap price-to-book valuation of 0.48 times — 1 times price-to-book is usually considered fair value — and near $9 stock price, he may think his margin of safety is high, Johnson said.

Watsa will likely shrink the company down and focus it on its more profitable corporate services, but with this stock that path to success isn’t clear, he added.

At the very least, Johnson said Watsa likely wants to salvage the investment he’s already made in the company and that’s easier to do in private. “He wants to try and resuscitate the business out of the public eye,” he said, adding that this might be tough to do.

Whether it works or not, taking chances on unloved companies such as BlackBerry can make a value investor a lot of money.

“You have to be patient and you also have to be willing to sell if you’re wrong,” Dupont said.

No comments:

Post a Comment